By Ivan Medenica

Ever since the coronavirus pandemic began and global physical distancing measures were introduced, many have been wondering about the consequences for theatre and the performing arts in general. As an art which is created and exists only through energy—the physical, spiritual and intellectual exchange between performers and the audience (the concept of “autopoietic feedback loop” of Erika Fischer-Lichte)—theatre cannot survive under the conditions that involve physical distancing. Even if we could devise a system to block some seats in theatre auditoriums, or to construct auditoriums in alternative venues, which would have an appropriate distance between the seats, not even the most bizarre imagination could come up with a mise-en-scène that would involve distancing, or actors’ physical play without–physical play… Still, this trepidation is unfounded, since theatre will–if not sooner, then in a year’s time for sure, once the vaccine against the coronavirus has been developed–return to its normal, non-distanced routine of production and distribution. The year 2020, however, might be lost when it comes to theatre after all.

With that in mind, a heroic dimension can be seen in the fact that one of the rare (grand) performances staged this year, at least among the ones I am aware of, bears the title 2020. It is a project by the Croatian director Ivica Buljan, which premiered 25 January 2020, based on the books by an intellectual star of today, Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari, made in coproduction with the leading theatre and cultural centres from Ljubljana, Slovenian National Theatre Drama, Ljubljana City Theatre, and Cankar Center. This project belongs to those seminal works of art which, not only by their title but by their content as well, point to the history of humankind encapsulated in one truly or imaginary important year: George Orwell’s novel 1984, Stanley Kubrick’s movie 2001: A space Odyssey, Ariane Mnouchkine’s performance 1789. Regardless of whether they represent dystopian futures or pasts that were once utopian, all those works used some other time dimensions in order to re-examine – the present. Just like Harari’s books, Buljan’s performance relies on the presentation of the past (Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind) and the projection of the future (Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow) to indicate the challenges that we are facing today, to point out at their origin, and the potential—although not necessarily optimistic—outcomes. That this performance is about the present is made evident through an excellent video by Vanja Černjul screened in the background, which consists of scenes from everyday life in various spots on the planet earth.

I did not manage to see the live performance; the lockdown was introduced just as I was about to travel to Ljubljana. Given the fact that we have begun to consider recordings of performances to be theatre, which is an approach that could be deemed problematic both from the point of view of performance studies and common sense, I too can toy with writing a text about a performance that I have seen only in the form of a recording. Since this text is more of a historiographic analysis than a critical review, its being based on a video-recording is not methodologically disputable. What reduces the problem even further is the fact that the recording I saw is of high-quality, comprised of both full shots (which are important for a performance with numerous group scenes and other spectacular sights), and close-up shots, while also registering the audience participation which is very important for the understanding of this particular poetics.

2020, directed by Ivica Buljan. Photo: Mestno Gledališče Ljubljansko (Ljubljana City Theatre).

The aim of this text is to analyse the artistic features of the performance (it belongs to the concepts of devised and immersive theatre), and their correlation with Harari’s texts, in order to support the thesis that the performance 2020 is an open call to us, the audience, to assume, in the spirit of the contemporary (post-dramatic) practices, our responsibility for theatre experience for which we share co-authorship but, at the same time, for the destiny of the world which we have also created. The post-dramatic paradigm implies the “aesthetics of responsibility,” which can also be found in the performance 2020. This is how Hans-Thies Lehmann defines “aesthetics of responsibility”: “Instead of the deceptively comforting duality of here and there, inside and outside, it can move the mutual implication of actors and spectators in the theatrical production of images into the centre and thus make visible the broken thread between personal experience and perception. Such an experience would be not only aesthetic but therein at the same time ethico-political.” (Lehmann 2004: 343)

An actor comes onto the vast empty stage of the Cankar Center and, as a narrator, introduces us to the thematic of the performance. The actor, Jurij Zrnec, is a good impersonator, which makes it clear to the audience that the narrator is not, as the stage logic and the text might suggest, Harari himself, but Slavoj Žižek. What additionally and wittily supports this conclusion is his costume: a T-shirt with an inscription that reads Antigone 2, which is a reference to Žižek’s first and, so far, only play, an adaptation of the Sophocles tragedy. The director Buljan and the dramaturg Petra Pogorevc have made the character of Žižek utter Harari’s leitmotif hypothesis: Homo sapiens might quite possibly be the most genocidal animal and/or human species (the Israeli scholar insists that sapiens is not the only human species in history). This strategy creates a blend between Harari’s thoughts and Žižek’s vocal expression, his typical excited, scattered, panting, unconventional way of speaking.

Although seemingly confusing, this approach is, actually, quite witty. While the quoted statement resonates in Žižek’s own thoughts and represents a director’s hint at local circumstances (the reception of Žižek’s person and work in his homeland, Slovenia), the fusion of these two identities also makes an ironical comment on the global phenomenon of celebrity-thinkers. Among them, namely, the Ljubljana thinker’s biggest competitor is the Jerusalem historian himself. And yet, the irony is not absolute. Zrnec’s acting fuses the irony with warmth for the Slovenian philosopher.

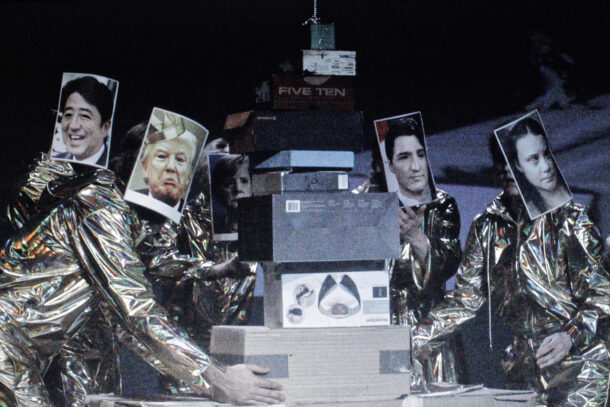

The prologue ends in a disturbing comment by Harari-Žižek, which announces the imminent end of humankind, for which sapiens is to take the blame because of the ecocide they have committed: “We, the small gods on this sad planet made of plastic.” The final outcry by the celebrity-thinker – “what’s this, an Odyssey 2020?” – is a witty introduction to the first part of the performance, which refers to the main thesis of the Harari’s “brief history of humankind,” the book better known by its title Sapiens. Namely, out of the depth of the stage, out of the trap where the smoke is coming from, the rest of the actors come in a throng, resembling in their appearance, movements and behaviour the monkeys from Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. In addition to the manner of their arrival on the stage, which represents a comical metaphor of humankind entering the stage of civilization from the depths of pre-historic times, the entire look of the actors (the costumes, masks, actions) is comically stylized: it is an ironical illustration of Homo sapiens in its genocidal rampage. Besides the stylization and its concomitant humor, the dominant feature of the prevalent part of the performance, in terms of style and genre, is its spectacular character. It is based on the performance of the songs and dynamic and attractive dance scores, but also on the use of stage machinery, resulting, among other things, in flying scenes. Among those who flew across the stage were Neil Armstrong (for obvious reasons), the hosts of the Tokyo Olympics (an equally obvious projection of a spectacular event which will, unfortunately, remain a projection), etc.

There is an unusual balance between the spectacular character of the performance and its opposite stylistic feature: minimalism. The stage design (Karmen Klučar and Ivica Buljan) is almost absent, and the space is mostly created through repositioning empty cardboard boxes and their metaphorical rearrangement, which is performed by the actors. Well conceptualized costumes by Ana Savić Gecan are stylized by the fabric they are made of (usually the one widely used by humans to destroy the planet: plastic), and by the shape, while sometimes they also demand the actors’ intervention in order to be fully realized onstage. Still, it is not only this minimalistic stage (and to a certain extent the costumes, too) that the actors shape; they also participate in the creation of their spoken text and stage movements.

2020, directed by Ivica Buljan. Photo: Mestno Gledališče Ljubljansko (Ljubljana City Theatre).

This brings us to the main poetics of the performance, which is at the same time its basic concept. The performance 2020 is not a dramatization of Harari’s texts. all of which serve only as a dramaturgical starting point.

As a work of devised theatre, the text was created through a process that combined Harari’s texts, the material previously chosen by the actors, and the text through the rehearsals. The final text was composed through an associative conjoining of all the materials by Pogorevc. To illustrate a text created thus, I will single out one of the scenes I found most impressive, the confession by the young actor Timon Šturbej. He follows Harari’s presentation of discrimination among the sapiens by a story of how, back in his school days, everyone, including him, used to avoid a Romani girl by the name of Gultena at parties. So now, from the greatest theatre stage in Slovenia, he apologizes to her, sincerely and through the tears (both in his and in our eyes). This example serves to demonstrate Buljan’s concept: the performance is not an illustration of Harari’s pondering the destiny of the humankind, but a dialectic confrontation with our, in this case the actors,’ experience of the topic.

Midway through the performance, the actors take a seat at the proscenium edge and engage in a dialogue with the audience. Having listed the annual death numbers in the world and the main causes, the biggest killer being the coronary diseases (the cause of 28 million deaths), seven times more than diabetes-related problems, and 280 times more than wars, the actors start asking the audience about their health. They do not address the audience as the characters they play but as themselves, and in a very personal manner (since it is not about collective phenomena but about personal health). All the points mentioned in the previous sentence are aspects of immersive theatre, the one which projects a more active audience participation. For that reason, this scene can be used as the best support of the thesis that, besides devised theatre, the other paradigm under which we can and should consider the performance 2020 is – immersive theatre.

Let us stay with this scene for a while. Although the questions seem spontaneous, and the actors do pose them in such a way, they are well thought out. The actors ask who in the audience has had a caesarean section, laser eye surgery, and an organ transplant, but also who is on antidepressants and who has had a plastic surgery. The fact that both actors and spectators appear to be answering the questions very truthfully, proves that the immersive quality of the performance, the penetration of artistic intention into the direct spectators’ experience, has been established.

And yet, this scene, cleverly devised in terms of dramaturgy and directing, goes a step further. The selection of questions about health suggests that modern medicine improves the quality of life (c-section, organ transplantation, etc.) but also meets the controversial challenges of modern civilization, such as craving eternal youth and beauty, or infinite happiness. It creates a clever link between the general immersive and post-dramatic features of the performance and the concrete topics raised by Harari, in this case particularly Homo Deus. This scene marks the beginning of the second part of the performance, which refers more to this book, and places its focus onto the current moment in the history of the civilization and the projection of its future, as opposed to Sapiens, which is focused on the past of civilization, and represents the basis of the first part of the performance. Unlike the thematic aspects of the two parts, the performance style remains the same. Therefore, this seemingly light, improvised, and spontaneous scene, methodically and accurately hits the bull’s-eye: Harari’s thesis that the concealed and ethically controversial, though understandable and to a certain extent justified goals of contemporary medicine and sciences–the perfection of human biological characteristics in order to achieve bliss, immortality and godlikeness–are always justified by the demands of conventional medicine: fighting illnesses and saving lives.

The last part of the performance, however, completely differs from the previous two, both in terms of genre and style, as well as the emotional impact it creates. As is the case with the excellent British television series Years and Years, which shares a similar spirit with the performance, it is not easy to determine whether the third part of the performance 2020 takes place today or in the near future, although the costumes, which are now realistic (unlike the stylized ones of the previous part), place it in the present moment.

2020, directed by Ivica Buljan. Photo: Mestno Gledališče Ljubljansko (Ljubljana City Theatre).

On the revolving stage, three TV studios are endlessly rotating, and three parallel interviews are taking place. In a Japanese garden, surrounded by his meditating adherents, Harari, in a slightly ironical form of a new-age guru (played by the excellent Marko Mandić) is giving an interview to Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook. The effect of strangeness and irony is amplified by the scenes in which everyone takes off their clothes, Harari and Zuckerberg engage in sexual intercourse, but, above anything else, by the appearance of a homeless woman. In her appearance and a total lack of interest in what is happening around her (Jette Ostan Vejrup, whose acting was marked by deep sophistication and distanciation) she creates a critical distance from the pretentious and at moments absurd conversation whose leitmotifs are marked by sentences such as: “one of the most important things is to get to know yourself better,” or “smell your finger–inhale, smell your finger–inhale.” Toying with the boundary between the fictional and the real, that is with her personality (she hosts a TV show in real life, too), which is something she was doing throughout the previous part of the performance, Zvezdana Mlakar interviews the choreographer of this performance, Ahmed Soura from Burkina Faso. His story is based on suffering, challenges and struggle: but he has emerged from all of that as a winner, as a person filled with optimism and zest, the feelings he conveys to the audience. In the third studio, a group of Slovenians, although they could be any other people from the Balkans, or from Europe, or Homo sapiens in general, crammed on a narrow sofa, are having an argument about the nation and politics. Their physical closeness in the small space (in the small worlds) is occasionally contrasted to their ideological conflicts. Just like the homeless woman in the Japanese garden, the everyman in a grey suit, with a confused, absent, and scared face (minimalistic acting by Matej Puc), keeps out of the conversation. Thus creating a distance from always the same, pointless, aggressive, monologic discussions that never reach any conclusion. Still, his position represents not only his detachment and non-belonging, but also the endangered position that often comes from non-belonging to the pack: at the end of the interview he falls victim–he suddenly drops dead.

At one point, all the studios remain empty, but the stage keeps revolving. The scene creates a strong metaphor of a possible civilisational perspective: the stage without actors keeps revolving just like the earth will keep rotating once it gets rid of us, Homo sapiens. This interpretation of the final image should not create the wrong impression. Not even the ending, not even the entire third part of the performance is a rounded, straightforward “stage metaphor;” on the contrary, it is distanced, absurdist, ambiguous. The third part is a randomly assembled kaleidoscope of possibilities that open up to humankind in the present moment of crisis. Those possibilities range from old, barren, (self)destructive nationalistic conflicts of the twentieth century, to the trendy new-age problematizing of reality, to an optimistic streak created through a brave struggle against real life challenges. Which of these—or of some other—we choose, and whether the choice would help us avoid or, actually, initiate the global finale hinted by the empty revolving stage (rotation of the human-free planet), depends solely on us–theatre audiences, the members of a certain society, people on earth. In other words, the empty revolving stage is not a “conclusion,” or a “verdict.” It is an open call to the spectators to come up with an ending: to assume responsibility for the destiny of the stage fiction, just like they must assume in relation to our reality, the one represented through this work of fiction.

Ivan Medenica (PhD) is a professor of the history of world drama and theatre at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade. He is an active theatre critic and has received the national award for the best theatre criticism six times. He is a member of the International Association of Theater Critics’ Executive Committee and the Director of its international conferences. Medenica is the artistic director of Bitef (Belgrade International Theater Festival).

European Stages, vol. 15, no. 1 (Fall 2020)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Philip Wiles, Assistant Managing Editor

Esther Neff, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 74th Avignon ‘Festival,’ October 23-29: Desire and Death by Tony Haouam

- Looking Back With Delight: To the 28th Edition of the International Theatre Festival in Pilsen, the Czech Republic by Kalina Stefanova

- The Third Season of the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano” – Theatre of Europe, Under the New Direction of Claudio Longhi by Daniele Vianello

- The Weight of the World in Things by Longhi and Tantanian by Daniele Vianello

- World Without People by Ivan Medenica

- Dark Times as Long Nights Fade: Theatre in Iceland, Winter 2020 by Steve Earnest

- An Overview of Theatre During the Pandemic in Turkey by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Frankfurt by Marvin Carlson

- Blood Wedding Receives an Irish-Gypsy Makeover at the Young Vic by María Bastianes

- The Artist is, Finally, Present: Marina Abramović, The Cleaner retrospective exhibition, Belgrade 2019-2020 by Ksenija Radulović

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2020