By Tony Haouam

2020 would decidedly be a year unlike any other. Long before the first mention of the novel coronavirus, the theme of this year’s Avignon Festival was—almost prophetically—Eros and Thanatos, the gods of desire and of death. The Covid-19 pandemic, however, had other plans: in the end, the Festival was simply canceled. As those who have attended the Festival in Avignon in July know, it is impossible to maintain social distance in the bustling streets of the city’s center, itself held tight by 14th century ramparts that enclose it. Within both the maze of small medieval streets and across 19th century avenues, actors distributing fliers for their productions in the “Off Festival” normally mix with crowds of amused onlookers, hurrying off to pack into the Court of Honor in the Papal Palace, a 2,000-seat venue. The virus, then, succeeded in killing the Festival: nonetheless, the desire to survive is so strong—so transforming—that the Festival metamorphosed into “A Week of Art,” a change in name in homage to Jean Vilar and the very first theatre event held in Avignon in September 1947. Maintaining this program is an “act of resistance,” as the Festival director Olivier Py explains, but it is an act that comes at a price: the financial loss is estimated at 130 million euros, and of the 45 performances programmed for the summer, only seven were able to be retained for this autumnal week of art, unique in its genre. From reimagined Noh theatre and experimental flamenco to a rewriting of the Orpheus myth accompanied by Monteverdi’s Orfeo, the performances of the Week of Art affirm a desire to live and to be reborn despite the death that surrounds us—a desire very appropriate for our current moment—and perhaps a reason that music occupies a significant place in most of the performed works, as if to compensate for the ineffectiveness of language to name the crisis that humanity is currently traversing.

It is, thus, a very strange opening ceremony that takes place Friday, October 23: the streets of Avignon are deserted, the sky is overcast, the temperature low, only a few people occupy the restaurant terraces, watched over by concerned owners. It is worth noting that nearly half of the inhabitants of Avignon support themselves through the tourism industry; for them, 2020 is a dark year. And moreover, on the eve of the opening of the Week of Art, President Emmanuel Macron announced a nationwide curfew from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m., which forced the Festival organizers to reprogram all of the performances for three hours earlier in the day, in order to allow spectators the time they need to return home after the shows. All of these setbacks, however, only demonstrate the theatre’s capacity to survive despite public health and political constraints. Maurice Jarre’s trumpets sounded, as usual, before each performance, but were accompanied by a message reminding spectators of the public health measures in place: obligatory masks for the duration of the performance and an empty chair between each spectator. Fortunately, these did not prevent the works from transporting spectators both very far—to Spain, Japan, or further still, Africa—and very near—to examine our current preoccupations, in order to better exorcise them.

The play featured in the opening ceremonies, without a doubt the most audacious work of the Festival, is a loose adaptation of the Orpheus myth, entitled The Game of Shadows, directed beautifully by Jean Bellorini in collaboration with Thierry Thieû Niang. Valère Novarina, who rarely accepts to write commissioned work, created the text especially for the Week of Art. The Game of Shadows was originally meant to be presented in the Honor Court, but due to Covid-19, the performance took place at La FabricA. Bellorini, by constructing a work in which Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo (1607) resonates with Ovid’s Metamorphoses, aims to respond to the following question: why does Orpheus, the son of Apollo, who was capable of convincing the guardians of Hell to let him rescue his wife Eurydice from their realm, turn around even though he knows that this means losing her forever? If Orpheus turns around, it is because he takes the risk of living fully, passionately, rather than in a prudent or “sanitized” manner: instead of “under-living,” Orpheus prefers to “over-live,” explains the director. (press conference).

The Game of Shadows, by Valène Novarina, directed by Jean Bellorini. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

For the duration of the 2 hour and 15 minutes, Novarina’s language is deafening, sometimes incomprehensible for being cumulative, verbose, elevated, and full of paronomasia (“I will trace with a compass the invisible limit between being born [naître] and not being (born) [naître/n’être pas],” says Orpheus, played by François Deblock), almost as if it were a foreign language. Some audience members even allowed themselves to check their phones during long sections of dialogue. But this language, thanks to its neologisms and dramatic intensity, transforms the actors into terrestrial creatures situated between the dead and the living, a place where each word is pronounced like a last breath, a final expiration. The nine actors wander about the stage, which gradually transforms into a liminal space, a space between Earth and Hades, where one desperately seeks to speak in order to avoid the workings of death. Words are revealed to be, at the same time, useless and vital, as the conflict is in the language and “death has nothing to say” because “it is worthless.” The best section of the text remains the very long enumeration of different conceptions of god—according to Gainsbourg, Nietzche, Artaud, Lacan, Darwin, John Lennon, Marie Curie, or still the Qur’an, and so on—recited with impressive energy by actor Marc Plas, who sent the audience into fits of laughter several times.

The staging and costumes by Macha Makeïeff make The Game of Shadows truly splendid. Framed on an empty stage there are, stage right, the nine actors—Eurydice in her wedding gown and Orpheus in a costume drawn on his body, a kind of skeleton—stage left, there are seven musicians and two singers (Ulrich Verdoni et Aliénor Feix), whose stupendous voices punctuate the dialogue with music from Monteverdi’s marvelous opera. The scenography is marked by visions alternately baroque and surrealist. Dilapidated, hollowed out pianos, travel the length of the stage, lit by red ghost lights, from behind which characters appear or disappear, until fiery footlights light the stage and then turn out to illuminate the audience. While Aliénor Feix sings, text is projected onto a red-toned backdrop: “My wish for tomorrow is that it will have happened”—a veritable incantation for the desire to live to transcend a universe haunted by death.

The Game of Shadows, by Valène Novarina, directed by Jean Bellorini. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

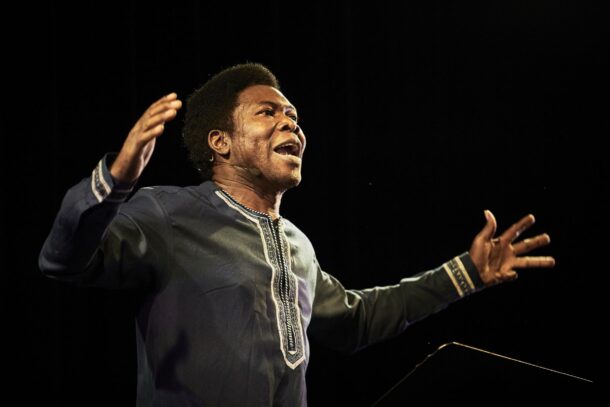

Rebirth through the word is also the driving force in Traces. A Speech to African Nations. This mise-en-scène is much more stripped down: the Burkinabe actor and director Étienne Minoungou stands alone, behind a podium, and directly addresses the audience with a playful tone and smiling eyes. Dressed in a black pagne, he is accompanied on his right by the musician Simon Winse, who plays the musical bow or the Peule flute. Minoungou performs, with much humor, a text written by Senegalese author-scholar Felwine Sarr, periodically calling out to spectators, encouraging reactions from the audience. If Novarina’s language is mysterious and hazy, language is above all a question of power and politics in Traces: “I have won the right to Speak. It was denied to me for ages. (…) I must speak to you, you, my fellows, because only the word remains.” For nearly an hour, Minoungou recounts the course of his life after leaving Africa, before returning to bring a message of hope. It is a matter, for the actor, of reconfiguring the imaginary associated with Africa, by retracing another political and philosophical history of the continent—from its pre-colonial period to the fatal migratory crossings of the Mediterranean today. Multiple conceptions of “Africanness” are evoked, and then questioned, one after the other: Négritude, Afro-pessimism, Afropolitanism, decolonization, Pan-Africanism, universalism, Afrofuturism. Blame circulates, as well, falling on either Western colonizers, fratricidal wars among African nations, the corruption that underpins capitalism, or still, predacious multinational corporations. The registers shift constantly during the play: when Winse begins playing the Peule flute with intensity, the actor’s rhythm accelerates—becoming more tragic, notably when evoking the deaths of Africans during the period of the slave trade—only later to break out into laughter again, asking the spectators, “Are we crazy?”—to which the audience, applauding energetically, responds chorally, “No!”

Traces: A Speech to African Nations, by Felwine Sarr, directed by Étienne Minoungou. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Throughout his performance at the Lambert Collection, the storyteller addresses his “brothers,” implicitly encouraging the whole of his Avignon audience, the majority of which was white the day I attended, to put themselves in the position of the Africans to whom Minoungou was speaking. It is this ambiguity between the imagined and the real audience that lends Minoungou’s performance such force. Insisting on Africa’s role as the mother of humanity, the actor implicitly invites us, regardless of our racial identities, to identify with our African “brothers.” He, furthermore, underlines the importance of “naming our world anew” by emptying it of dehumanizing terms (like “underdeveloped”), all while maintaining the memory of our slave or migrant brothers, in order to imagine together a universe filled with “traces” of life—that is of laughter, of the desire for freedom, of vibrations. These traces alone can allow our own re-humanization. If the language of the past created violence, then a new language, as well as the transmission of history to our younger generations, will deliver us from it. “We must remember,” explained Minoungou, “to rise up against enslavement.” Despite the sometimes difficult, but true, picture of human history—slavery, genocide, armed conflicts, venality—Minoungou succeeds at cleverly juxtaposing death and hope, sorrow and laughter, thanks to a rich performance, grounded in the body, as well as to a powerful musical prosody that led a large portion of the audience to rise to their feet in applause at the end of his performance.

Traces: A Speech to African Nations, by Felwine Sarr, directed by Étienne Minoungou. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Another performance earned the most enthusiastic standing ovation of the Week of Art: Melizzo Doble, or “Twin double,” which staged a fantastic and wild duo, the danser Israel Galván and the singer Niño de Elche (the duo which had already collaborated on Fiesta during the 217 Avignon Festival). Programming a flamenco performance for this Week of Art is particularly appropriate: this musical genre and this dance form, born within marginalized communities in Andalusia and highly anti-establishment, are haunted by the literary topoi of death and of loved ones—even the state of desiring someone to the point of agony. In Melizzo Doble, the Adalusian duo reimagines some of the flamenco genres (martinetes, seguiriyas, pregones, bulerías, tangos, farrucas, caña) and turns to traditional flamenco topoi—such as litany, social oppression, imprisonment, unrequited love, and toponymic references to the south of Spain.

Melizzo Dole, by Israel Galván (dancer) and Niño de Elche (singer). Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

In the theatre “Benoît XII,” spectators wait impatiently in front of a nearly empty stage—occupied only by a metallic disk, a felt square, a wooden pedestal, and a chair—until Niño de Elche, dressed entirely in black, sings the first note, plaintive and harrowing, unleashing immediately the zapateado (the striking of the ground) of Galván’s white boots. The dancer, for his part, is dressed in black overalls like that of coal miners. The audience, however, was startled by the lack of supertitling for this performance done entirely in Spanish, but they quickly ended up being captivated by the intensity of de Elche’s singing, his way of playing with traditional flamenco songs’ format by deconstructing them, ad-libbing at times, and by punctuating some singing parts with rumbling sounds and onomatopoeias. Next to him — or rather, around him — Galván follows the rhythm of the song in perfect sync with hypnotizing dance moves and palmas (hand-clapping), hitting all the objects on stage, including his own body and Niño de Elche’s back. With a mischievous smile on his face, Galván ceaselessly looks at the audience, while combining flamenco dance steps with voguing and slapstick body movements. The chemistry between the two artists is staggering, to the point where we don’t know who, between the singer and the dancer, leads the dynamic rhythm of the performance. Together, they pave a new way for experimental flamenco.

For an hour and a half, the two artists perform a series of songs (palos) with surrealist-sounding titles: Fandango cubista, Seguiriyas carbónicas, Sevillanas sentadas… But thirty minutes before the end, the lights shut down completely and both actors go silent. Then, very slowly, two spotlights are switched on: one lights up Niño de Elche’s face while the other illuminates Galván’s boots striking frantically on the metallic disk. He dances on it so hard that it turns into dust, creating on stage a grey smoke, symbolizing the ashes of the loved one for whom Niño de Elche sings a mournful incantation. Galván throws himself on the ground, onto the metallic ashes ; the sound of the gravel accompanies the singer’s cry. In the room, the tension reaches its acme. It is, by far, the most beautiful scene I have witnessed during the Week of Art.

Melizzo Doble, by Israel Galván (dancer) and Niño de Elche (singer). Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

Yet again, after death life is reborn, as though the energy of the two artists had managed to defy agony. Thanks to the fantastic work of lighting director Benito Jiménez, the lights come back up, fully bright and red, illuminating the duo who appear even stronger and goofier, playfully smiling at each other. The “fraternal twins,” as they like to call each other during interviews, seem happier than ever to have found each other again, before chanting La Malena, the last song of the show, concluding their performance with a powerful and heartfelt: “Olé!” According to Galván and de Elche, this performance is like “an apartment shared by two roommates;” to us the audience, it felt like a vigorous love declaration to the universal and transforming power of music and dance. As one French spectator told me at the end of the show: “I don’t speak Spanish, but I feel like I understood everything.”

The Damask Drum is another performance that relies on a tight collaboration between two artists. Actress and dancer Kaori Ito and actor Yoshi Oïda stage Yukio Mishima’s adaptation of “Aya no Tsuzumi,” a 15th century traditional Noh play. Originally, the plot is simple: an old man falls in love with a young woman, who gives him a damask drum and tells him: “If you manage to sound the drum, I will be yours.” But in The Damask Drum, our two actors offer a modern interpretation of this Noh story where amorous feelings are replaced with a more ambiguous form of desire, situated outside the realm of sexuality.

The Damask Drum, adapted by Yukio Mishima, directed by Kaori Ito and Yoshi Oïda. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

The pink damask drum, shaped like an hourglass, is on a small wooden stool at the forefront of the set, next to a shadeless lamp that is turned on. Stage left, there is a desk, a chair, and a mirror that look like an actor’s dressing room. Stage right, we can see a multitude of mainly Japanese traditional instruments — Nô-kan bamboo flutes from Noh and Shinobué theatre, taïko and shimé-daïko drums, a také-marimba bamboo xylophone, as well as a South-American quéna flute. All of these instruments will be played by musician Makoto Yabuki throughout the performance. Oïda suddenly appears on stage, wearing a beige trench-coat and carrying a water bucket, and starts mopping the floor of what seems to be a theatre decor. While mopping, he plaintively recites, almost as though he were in agonizing pain, a verse written by Jean-Claude Carrière for the play: “Suffering, birth, life” [Souffrance, naissance, la vie]. Then, Ito arrives on stage, all dressed in dark pink, with a T-shirt and yoga pants; she puts a beautiful light-pink kimono on the back of her chair while she’s getting ready for a dance performance, framing The Damask Drum as a dance rehearsal replete with meta-theatre elements that shed a modern light upon the 15th century Noh story.

Ito is warming up by executing some dance moves, under the cleaning man’s amused yet envious eyes. Why does he gaze at her so intensely? What is this desire that we can read in his eyes? The dancer looks back at him, bursts into laughter, and then invites him to come join her; he refuses, he is too old, but she insists anyway. The cleaning man accepts and what follows is a very heartwarming choreography scene where the old man, whose physicality is slightly clumsy yet touching, tries to follow the lead of the dancer’s cadenced and flowing dance rhythm. Their shadows are poetically reflected on the back wall of the Chapel of White Penitents, covered for the occasion with a large white silk cloth. This intergenerational dance is so moving — the audience looked smitten and even gasped at times — that it gives the impression that it is still possible to dance, even at the winter of our lives (Yoshi Oïda is 87 years old!) if we still feel the driving force of desire.

While the old man exits the stage, frustrated to not have been able to strike the damask drum, he says to the dancer: “You have been making a fool out of me. You are cruel.” The dancer ignores him, focused on the Rambyoshi — a traditional “madness dance” that Ito learned from a Noh master — that she is about to perform. The choreography, which consists of a lot of grounded body movements, is impressive, as the dancer gracefully moves around the damask drum. Each one of her dance moves perfectly mirrors the music played by Yabuki. We will never know if the damask drum will ever sound one day: but it works as a poetic metaphor for troubled desire, for a promise of something that might never happen but still drives us to fight against the ineluctability of time. “Suffering, you dance, I live” [Souffrance, tu danses, je vis], happily concludes the cleaning man to the dancer — a nice echo to Mellizo Doble but also to the hope that Minoungou expresses towards African youths.

The Damask Drum, adapted by Yukio Mishima, directed by Kaori Ito and Yoshi Oïda. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

During a roundtable after her performance, actress Ito insists that she wanted to shy away from the traditional image of Japan and avoid portraying a caricature of the passive Japanese women. For that, the result is successful, but the overall impression left by this one-hour and fifteen minute long performance is a feeling of incompletion and haziness. Some elements of the play are unclear — for instance, why does the cleaning man reappear wearing a white scrub covered with blood ten minutes before the end? A very eager high-schooler asked actor Oïda about this, but his response remained evasive: “You are the one who does the interpreting, not me!”

On Wednesday October 27th, even though there are still 4 days of plays left, President Macron announces a nationwide lockdown starting the next day at midnight. Then, we find out that the adaptation of Moby Dick, directed by Norwegian puppeteer Yngvild Aspeli, is cancelled because one of the actors has been tested positive for covid-19. The end of the world is approaching, and there is only one performance left to see before another confinement: Endless Andromaque, an adaptation of Racine’s play directed by Gwenaël Morin, with the help of Barbara Juig as his artistic partner. For this play, Morin asked the three young actors from “Ier acte”—a theatre program that gathers actors from minority groups and low-income families—to learn, by heart, the entirety of Andromaque, that is, 1,648 Alexandrines. Each day, the actors switch roles and play a different character: it is a Herculean task, with endless possibilities, that they perform under Juig’s attentive eye, who plays the role of a conductor who strikes a drum between each scene, and sometimes serves as the prompter for the young actors. The story of Andromaque — one of the most performed plays in France — is simple : “Oreste loves Hermione, who loves Pyrrhus, who loves Andromaque, who loves her son Astyanax and her husband Hector who died.” A structure of unrequited and hopeless desire chain that drowns all of the characters far into despair.

Since Endless Andromaque is a wandering performance that aims at inclusivity, its venues change every day, each time in a little village in the outskirts of Avignon. Today, the play is performed at the Sorgues cultural center. Once we enter the room, we are given the entirety of Racine’s play (slightly rewritten and rearranged) on a yellow newsprint. The room is quite small, there are two groups of chairs on each side, and the stage is in the middle, composed with only four chairs and a drum: the theatrical set-up reminds us of an agora. The decoration on the walls is quite sparse: there’s a master painting printed on paper representing a Trojan horse, a map of Ancient Greece drawn with a marker, and the allocation of the play’s roles. The atmosphere in the room is certainly nervous, most of us know that this is probably the last play we are going to see for a while.

Endless Andromaque, by Racine, directed by Gwenaël Morin. Photo: Christophe Raynaud de Lage.

From the first drum blow, the actors, all wearing jeans and sneakers, recite the Alexandrines so fast that it is impossible to understand everything: the audience members have to frequently read their text-newspapers to follow the plot. The actors don’t play much with the stage space, even if they sometimes walk around the audience to get on a chair and point to the map of Epirus that is hung on the wall. Admittedly, the acting is impressive regarding the emotional embodiment — a special mention to Emika Maruta, who delivered a breathtaking performance of Andromaque and Oreste. But despite some moments of grace, Endless Andromaque was arguably the least successful play of the Week of Art. Almost a quarter of the audience members left the room before the end of the play, probably perturbed by the actors’ overly expeditive prosody. Director Morin justifies his formal choices by explaining that he wanted to question hegemonic forms of culture, and the role they play, by transforming them endlessly and putting them in contact with the immediacy of the present. “We must accept to not understand Racine” says the director.

In many ways, this Week of Art felt like an intimate event: very few people in France even knew that there was still a theatre event happening in Avignon this year despite the pandemic. The limited number of tickets available made it easy to run into someone that we had come across the day before, while waiting in line to get in. And if we pay attention to the spectators’ ways of speaking, we realize that the audience’s demographic has changed: we barely can hear any Parisian accent or foreign languages. Most of the audience members seem to be retired people from the South of France or students from the city’s neighbouring high schools. Avignon feels like a village now, just like in 1947. Sure, the masks remind us that it’s 2020 and that we live with a pandemic; yet, as everyone hurryingly leaves Avignon, it is now with an even stronger desire to get over the deadly virus in order to be able to finally live again.

Tony Haouam is a joint PhD candidate at NYU’s Institute of French Studies and Department of French Literature, Thought and Culture. His research focuses on the intersection of race, humor, and emotions in contemporary France. His dissertation, “Laughing at Color Blindness: Race, Performance, and Affect in the French Comedy Scene,” examines stand-up comedians’ aesthetic work in order to get at the subtlety of the corporeal, sound, performative, and rhetorical modes through which race and racialization operate and are interpreted in ‘colorblind’ France. He is currently at the École Normale Supérieure d’Ulm as a pensionnaire étranger, conducting ethnographic research on controversial comedians and their public.

European Stages, vol. 15, no. 1 (Fall 2020)

Editorial Board:

Marvin Carlson, Senior Editor, Founder

Krystyna Illakowicz, Co-Editor

Dominika Laster, Co-Editor

Kalina Stefanova, Co-Editor

Editorial Staff:

Philip Wiles, Assistant Managing Editor

Esther Neff, Assistant Managing Editor

Advisory Board:

Joshua Abrams

Christopher Balme

Maria Delgado

Allen Kuharsky

Bryce Lease

Jennifer Parker-Starbuck

Magda Romańska

Laurence Senelick

Daniele Vianello

Phyllis Zatlin

Table of Contents:

- The 74th Avignon ‘Festival,’ October 23-29: Desire and Death by Tony Haouam

- Looking Back With Delight: To the 28th Edition of the International Theatre Festival in Pilsen, the Czech Republic by Kalina Stefanova

- The Third Season of the “Piccolo Teatro di Milano” – Theatre of Europe, Under the New Direction of Claudio Longhi by Daniele Vianello

- The Weight of the World in Things by Longhi and Tantanian by Daniele Vianello

- World Without People by Ivan Medenica

- Dark Times as Long Nights Fade: Theatre in Iceland, Winter 2020 by Steve Earnest

- An Overview of Theatre During the Pandemic in Turkey by Eylem Ejder

- Report from Frankfurt by Marvin Carlson

- Blood Wedding Receives an Irish-Gypsy Makeover at the Young Vic by María Bastianes

- The Artist is, Finally, Present: Marina Abramović, The Cleaner retrospective exhibition, Belgrade 2019-2020 by Ksenija Radulović

www.EuropeanStages.org

europeanstages@gc.cuny.edu

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center:

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

The Graduate Center CUNY Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York NY 10016

European Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2020